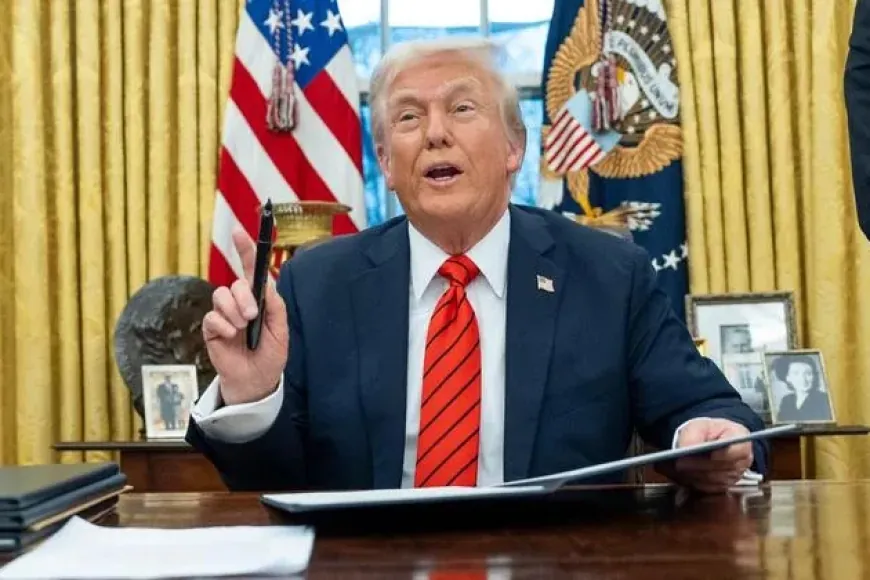

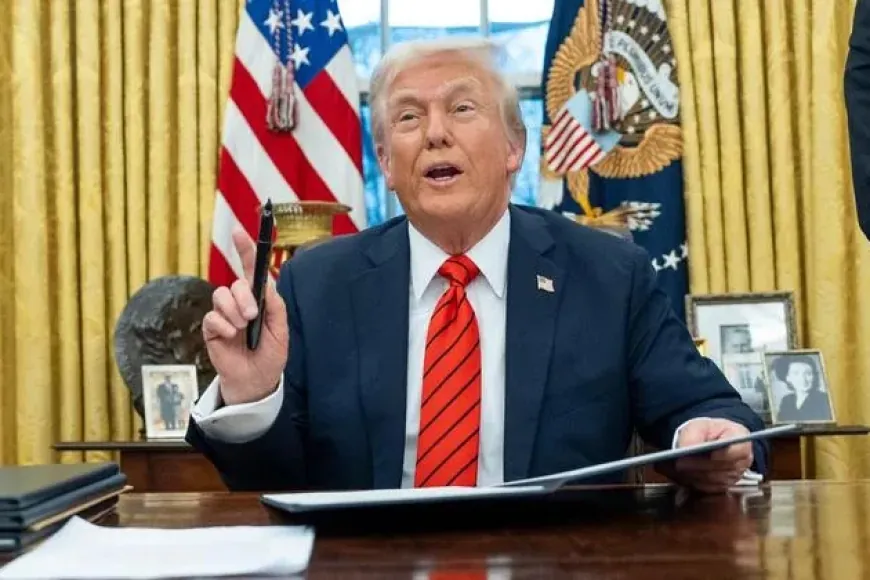

President Donald Trump has declared that the fight against inflation is over, pointing to lower mortgage rates and cooling consumer prices as proof that his administration’s economic strategy is working. But for millions of Americans, that message doesn’t quite match what they’re seeing at the checkout counter.

Inflation, though lower than its pandemic-era surge, has picked up again in recent months. Data shows prices have climbed in three of the last four months and sit slightly higher than a year ago. Still, both the White House and the Federal Reserve have adopted a more confident tone, signaling that they believe the worst is behind.

Speaking before the United Nations General Assembly in late September, Trump said, “Grocery prices are down, mortgage rates are down, and inflation has been defeated.” Around the same time, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell highlighted that inflation had dropped sharply from its highs and that the risks of renewed price spikes appeared to be fading. Shortly after, the Fed made its first rate cut of the year — a move that underscored its growing faith in economic stability.

However, not everyone shares that optimism. Inflation remains above the central bank’s 2% target, and surveys show many households still feel squeezed. For the administration, that disconnect poses both political and policy challenges. For the Fed, cutting rates while inflation lingers above target could weaken its credibility as a price stabilizer.

Economists warn that the recent wave of U.S. tariffs could complicate the picture. The administration expects the duties to have only a short-lived effect on prices, but if inflation proves more stubborn, the decision to loosen monetary policy could backfire. Once people and businesses start doubting the Fed’s ability to maintain price stability, they often act in ways — such as demanding higher wages or raising prices — that make inflation harder to contain.

Karen Dynan, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, recently noted that the memory of the post-pandemic price surge remains vivid for most Americans. Combined with new trade barriers, that uncertainty could reignite inflation expectations. “If confidence slips, these rate cuts will look premature in hindsight,” she said.

Official data shows consumer prices were up 2.9% in August from a year earlier, compared to 2.6% the year before. That’s far below the 9% peak of mid-2022 but still a long way from the Fed’s comfort zone. The September inflation report, delayed by the partial government shutdown, is expected to provide more clarity.

The administration’s tariff strategy has already pushed up prices for several imported goods, from household appliances to holiday decorations. Furniture and durable goods costs rose roughly 2% year over year in August — modest, but notable after decades of steady or falling prices. Grocery bills have climbed at their fastest non-pandemic pace in nearly a decade, with coffee prices jumping sharply amid droughts in producing countries and new import taxes on Brazilian beans.

Fed policymakers remain divided on whether the inflation threat has truly eased. Minutes from their latest meeting show concern that higher tariffs could prolong price pressures, even as unemployment risks increase. “It’s a gamble to assume these shocks will be short-lived,” warned Jason Furman, a Harvard economist and former presidential adviser. “Three percent inflation used to be a big deal — and it still should be.”

Meanwhile, Trump has doubled down on trade restrictions, recently announcing steep tariffs on a range of goods — including pharmaceuticals, kitchen cabinets, and trucks — while threatening further penalties on Chinese imports. The ripple effects are already evident: major consumer brands have announced new price adjustments to offset costlier materials.

Chris Butler, who heads National Tree Company — the country’s largest artificial tree producer — said his firm expects to raise prices by about 10% this holiday season. “Neither we nor our suppliers can absorb the full tariff impact,” he explained. “Some of it inevitably reaches the consumer.”

Federal Reserve officials acknowledge the delicate balance they face. Jeffrey Schmid, president of the Kansas City Fed, emphasized that preserving credibility is key: “History shows that inflation born from lost confidence is far tougher to reverse.”

Others remain cautiously hopeful. Stephen Miran, a recent Trump appointee to the Fed’s board, said that easing rental costs and reduced consumer demand from lower immigration could cool inflation pressures in the coming months. “I think we’re moving in the right direction,” he said. “It may just take time for people to feel it.”

Across the country, households are still adjusting to higher costs that don’t match the White House’s upbeat tone. Families in cities and small towns alike say grocery trips remain expensive, rents are only slightly lower, and monthly budgets feel tighter than they did a few years ago. While the administration points to falling rates and slowing inflation as signs of progress, most Americans see those improvements as modest — not yet enough to ease the strain on their wallets.

Also Read: Trump Threatens Massive China Tariffs, Doubts Meeting with Xi